All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

A Real-world Study Comparing Atropine Monotherapy vs. the Combined Treatment with Peripheral Defocus Lenses and Low-dose Atropine

Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate whether the combination of low-dose atropine (LDA) and peripheral defocus lenses (Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segments, DIMS) provides additional benefit for children undergoing myopia management.

Methods

This was a retrospective study including fifty-one patients aged 8 to 13 years who attended a private clinic between January 2020 and September 2021. Subjects were selected based on documented myopia progression of ≥0.50 D/year during the previous 12 months. Following the initial diagnosis of myopia, participants were advised to spend at least 2 hours per day outdoors for 6 months (Phase 1 – environmental control). If axial length (AL) increased by > 0.15 mm during this period, participants were prescribed nightly LDA (0.025%) for the following 12 months (Phase 2 – monotherapy). If, at the 12-month visit, AL continued to increase by > 0.17 mm/year, combination treatment with LDA and DIMS lenses was initiated for a further 12 months. Only data from the right eye were analyzed. Treatment efficacy was evaluated by comparing the differences in myopia progression across the treatment periods.

Results

The mean age of patients was 10.16 ± 1.63 years. Males comprised 25 (49.02%) of the subjects. At baseline, the mean spherical equivalent refraction, median keratometry, and AL were -3.01 ± 1.22 D, 43.13 ± 1.19 D, and 24.60 ± 1.03 mm, respectively. At phase 1, the mean progression in AL was estimated to be 0.39 ± 0.09 mm/year. The combined treatment significantly reduced the progression of myopia compared to LDA monotherapy (0.21 ± 0.03 versus 0.13 ± 0.05 mm, p < 0.0001).

Discussion

The pharmaceutical intervention that is most frequently employed in clinical settings is atropine 0.01%. Nevertheless, a number of studies demonstrated low efficacy in the long term, particularly when AL elongation was the desired outcome. Additionally, it has been proposed that the most effective LDA tested in the young Asian population is 0.05% atropine; however, in the Western population, there were reports of frequent side effects when using this LDA. The combined treatment using atropine 0.025% was one option to increase the efficiency of reduction in myopia progression.

Conclusion

The combination of DIMS spectacle lenses and LDA achieved the greatest reduction in myopia progression, as measured by axial length elongation, compared with LDA monotherapy or environmental control in this Brazilian population. Further randomized, double-blind clinical trials with longer follow-up are warranted to better determine the true impact of this combination therapy on myopia progression.

1. INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of myopia among adolescents has increased worldwide, particularly in urban Asian countries [1, 2]. Additionally, recent evidence shows that myopia rates are rising not only among teenagers but also in younger children, highlighting a concerning trend of earlier onset and more rapid progression in pediatric populations [3]. Some of these myopic children will get high myopia, which is associated with a significantly elevated risk of vision-threatening complications, such as retinal detachment, glaucoma, and myopic maculopathy [4, 5].

Myopia progression can occur from increased corneal curvature, the power of crystalline, or eye elongation [6]. Corneal myopia is associated with structural abnormalities of the cornea, lenticular myopia results from changes in the shape and/or index of refraction of the crystalline, and Axial myopia, the most prevalent form, is characterized by excessive elongation of the globe, particularly of the posterior segment [7-10]. Regarding this, myopia progression is associated with the lengthening of the eye [10]. In the medical literature, myopia that develops during childhood and adolescence as a consequence of axial elongation is known as school myopia [10-12]. This term distinguishes it from congenital or syndromic forms and reflects its multifactorial etiology, influenced by both genetic predisposition and environmental exposures-especially increased near-work activity and reduced time spent outdoors [10, 12, 13]. Axial length (AL) has been proposed as a key variable for predicting the risk of visual impairment due to macular involvement in high myopia [14, 5]. Therefore, monitoring AL, preferably through direct measurement rather than estimation from optometric parameters, which has been shown to be imprecise, is essential [15]. Efforts to prevent AL elongation during childhood and adolescence may reduce the likelihood of myopia-related retinal complications later in life [16].

In myopia management, there are many evidence-based interventions, used individually or in combination, with the aim of slowing AL growth and reducing the long-term risk of retinal disease associated with high myopia [4, 5, 17]. In recent years, some studies have reported that low-dose atropine (LDA) (0.01 to 0.05%) treatment has produced encouraging outcomes with minimal side effects and low myopic rebound [18-20]. Optical treatments, including orthokeratology, specialized ophthalmic lenses, and soft contact lenses incorporating peripheral myopic defocus, have shown promising results in slowing myopia progression [21-23]. However, each method has some limitations.

Recently, a novel spectacle lens with peripheral myopic defocus was introduced (MiYOSMART ®, HOYA Corporation) with Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segmsents (DIMS) [17]. A combination of LDA with DIMS, aiming at increasing the efficacy of myopia management, has been reported [24-26]. According to our knowledge, there have been no studies associated with atropine at a concentration of 0.025% (Part of this article (as an abstract in a poster has previously been published in 19Th International Myopia Conference, Sanya, China, September 2024) [27].

The primary objective of this study is to demonstrate the synergistic effect of DIMS lenses on patients using LDA 0.025%.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

This retrospective study reviewed the medical records of the first one hundred myopic patients aged 8 to 13 years who attended the Oftalmocenter Santa Rosa clinic in Cuiabá, Brazil, and who exhibited a myopia progression of at least 0.50 per year. The patients were selected if the first exam occurred between January 2020 and September 2021, and they needed to be on three sequential phases:

- Phase 1 environment control: Following initial myopia diagnosis, participants were advised to spend 2 hours a day in outdoor activities for 6 months.

- Phase 2 monotherapy - atropine 0.025%: Participants whose axial length (AL) increased by ≥ 0.15 mm in 6 months were prescribed atropine 0.025% for the next 12 months.

- Phase 3 combination treatment: If at the 12-month visit the AL increased by ≥ 0.17 mm/year, combination treatment (LDA + DIMS spectacle lenses) was prescribed for the next 12 months.

The selected patients needed to have a visual acuity better than 0.63 (logMar 0.2) in both eyes, a spherical equivalent of cycloplegic refraction (cyclopentolate 1% and tropicamide 1% twice, preceded by 1 drops of proximetacaine 0.5%), measured 40 min after the last drop with the autorefractor (Canon®, USA) between -1.00 and -5.00 D, and refractive astigmatism < 1.50 D, flat keratometry (K1) < 46 D, regular topography, and ocular optic biometry (Lenstar LS 900; Haag-Streit Diagnostics, Switzerland) with five repeated measurements, with a maximum inter-measurement standard deviation (SD) of no more than 0.02 mm. Each study phase had specific criteria that participants had to meet to be included in the final analysis. Phase 1 required K1 progression < 0.25 D and AL progression ≥ 0.15 mm over 6 months. In phase 2, the criteria were K1 progression ≤ 0.25 D and AL progression ≥ 0.17 mm per year. Progression during Phase 1 was estimated on an annualized basis for calculation purposes. Only the right eye was included in the analysis. Eligible patients were required to have a visual acuity better than 0.63 (logMar 0.2). Exclusion criteria included strabismus or binocular vision abnormalities, ocular or systemic disease, history of other myopia-control treatments, incomplete data, or a follow-up duration other than 365 ± 30 days.

All patients were attended to by the first author.

Atropine 0.025% was compounded by Citopharma in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. It has a pH of 5 and benzalkonium chloride 0.1 mg/mL as a preservative. The patients were instructed to apply an eyedrop at bedtime. The number of bottles used (two bottles, each 10 mL) was used to monitor the regularity with which they applied eyedrops.

The DIMS lenses were instructed to be used during all awake time, except for shower time.

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Centro Universitário da Várzea Grande, Brazil, under number 2127639 (December 8Th, 2023).

The data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 19.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The results for age, spherical equivalent refraction (SER), Km, and AL were described as mean, SD, median, and range inter-quartile. The Shapiro-Wilk W test was used to analyze the distribution's normality. The phases were compared using the Friedman test followed by the post-hoc test (Dunn with Bonferroni adjustment). A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

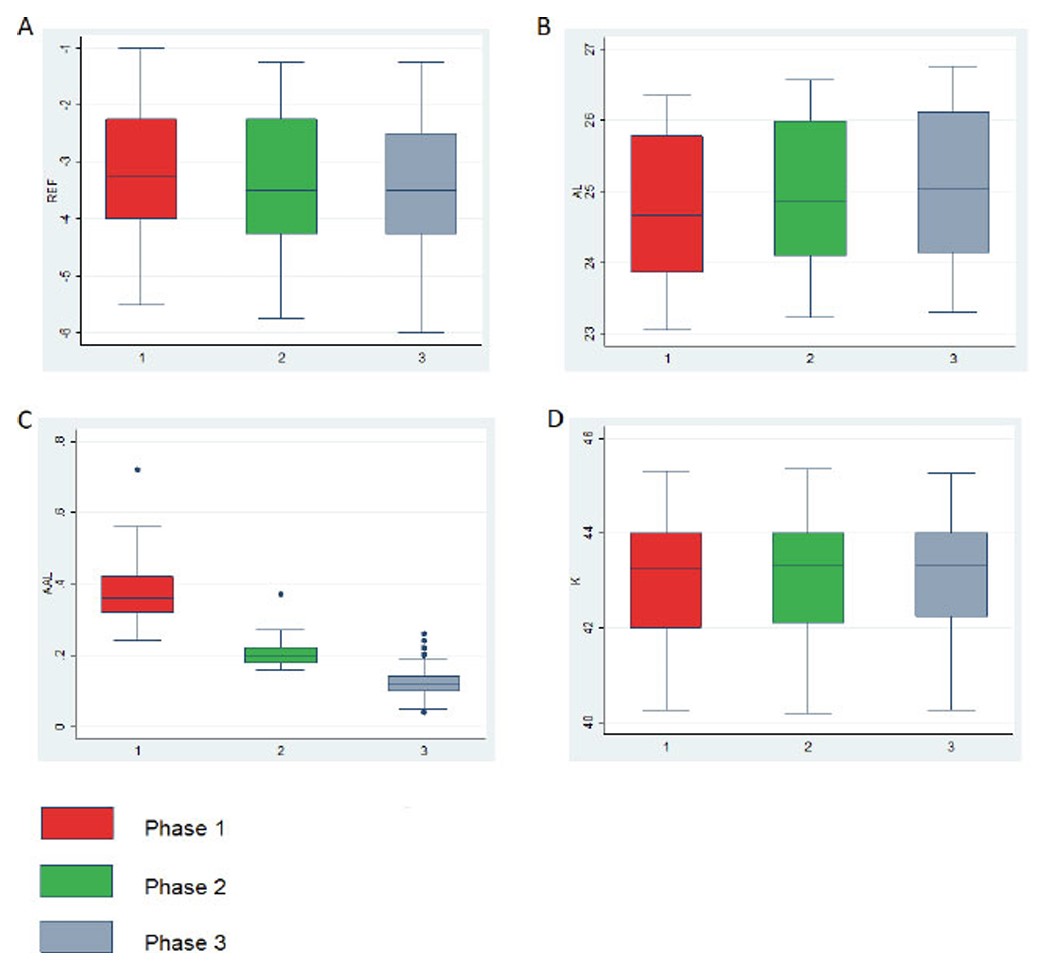

After excluding 49 patients who did not meet the specific inclusion criteria for the three study phases, a total of 51 participants were included, with a mean baseline age of 10.16 ± 1.63 years. Twenty-five (49.02%) were male subjects. The initial SER average and visual acuity were -3.01 ± 1.22 D and 0.98 ± 0.1 (logMar 0.008). The baseline data are shown in Table 1. The changes in SER, mean keratometry (Km), and AL were compared over the three phases shown in Fig. (1). The changes in AL were 0.39 ± 0.09, 0.21 ± 0.03, and 0.13 ± 0.05 mm in phases 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The Shapiro-Wilk W test demonstrated no symmetry and no normality of data. Statistical analysis showed that the increase in the AL over a period of one year was less pronounced in the combined phase (p < 0.0001). There were no significant differences noted between the three phases in Km (p 0.068). There were significant differences observed between the phase 1 and 2 in SER (p < 0.001).

4. DISCUSSION

Atropine 0.01% is the most widely used LDA pharmaceutical intervention in clinical settings [17]. However, several studies showed weak effectiveness in long-term follow-up, particularly when AL elongation was the outcome of interest [18-20, 28, 29]. Moreover, 0.05% atropine has been suggested as the most effective LDA tested in the young Asian population [20]. In the Western population, there were reports of frequent side effects when using this LDA [30]. In this study, AL elongation was 0.13 ± 0.05 mm/year with combined treatment, compared to 0.21 ± 0.03 mm/year from LDA monotherapy, confirming the synergistic effect between LDA and DIMS in this population.

| Outcome | Phase | Mean sd | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical equivalent | Baseline | 3.01 ±1.22 | |

| Refraction (d) | Phase 1 | 3.33 ±1.22 | |

| - | Phase 2 | 3.40 ±1.21 | |

| - | Phase 3 | 3.46 ±1.23 | |

| - | - | - | |

| Axial length (mm) | Baseline | 24.60 ±1.03 | |

| - | Phase 1 | 24.79 ±1.03 | |

| - | Phase 2 | 24.99 ±1.02 | |

| - | Phase 3 | 25.12 ±1.03 | |

| - | - | - | |

| Keratometry (d) | Baseline | 43.13 ±1.19 | |

| - | Phase 1 | 43.12 ±1.21 | |

| - | Phase 2 | 43.13 ±1.24 | |

| - | Phase 3 | 43.17 ±1.22 | |

Boxplot with the distribution of phase 1 (environmental control), phase 2 (LDA), and phase 3 (combined treatment) of refraction (A), axial length (B), variation (final AL – initial AL) (C), and keratometry (D).

Although this study used LDA at 0.025% in combination with DIMS, it did not show better results than those obtained in the European population (the Milan – Italy – study), which used atropine at a concentration of 0.01% and DIMS [24]. The reason for this could be attributed to the methods used for participant selection. In the Milan study, a combined group was selected from progressive myopes, while in this study, the participants were selected from progressive myopes in whom monotherapy was not effective. Therefore, these patients showed greater progression than in the Milan study.

A 2023 Chinese retrospective study reported the use of combined treatment for myopic patients with fast myopia progression (≥ 0.75 D/year). They used DIMS and atropine at either 0.01% or 0.05% concentrations. Only the group associated with atropine at 0.05% demonstrated significant myopia control [26].

Some studies have reported risk factors for fast myopia progression, including young individuals who are upset by myopia, parents who have myopia, refractive error < 4 D, AL > 24.5 mm, and a lack of outdoor activity [31-33]. One strategy for these cases could be starting a combined treatment, which could be studied in a clinical trial.

There are some limitations to this research. First, it was a retrospective study. There was no specific group; however, there were distinct phases that occurred in a particular order. The design was not randomly chosen or masked. The number of participants was not large enough. Furthermore, this study was conducted for only one year after the combined treatment.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the combination of DIMS spectacle lenses and LDA resulted in the most significant reduction in myopia progression, as measured by AL elongation, compared with LDA monotherapy or environmental control in this Brazilian population. Further randomized, double-blind clinical trials with longer follow-up are warranted to better determine the true impact of this combination therapy on myopia progression.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: C.M.C: Study conception and design; M.N.R, M.B.N, V.D.P.C, J.E.C.L.: Data recording; A.J. and A.S.: Methodology; C.M.C, J.T.C.: Validation; C.M.C, G.M., J.T.C.: Writing, reviewing, and editing; C.M.C, G.M.: Writing the original draft preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| AL | = Axial Length |

| SER | = Spherical Equivalent Refraction |

| UNIVAG | = Universidade de Várzea Grande |

| CAAE | = Certificado de apresentação para apreciação ética |

| K | = Keratometry |

| SD | = Standard Deviation |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was registered in the Plataforma Brasil Program– CAAE: 75825823.0.0000.5692

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All the humans were used in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013 (http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/node/3931).

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All participating students and legal guardians were oriented about the study, and those who agreed to participate, signed written informed consent.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.